Control Structures: Conditionals

Up until now, you've learned to make linear C++ programs, where the program executes every line of code you write. Sometimes the program will take a break to ask for user input, but the way it runs is pretty straightforward.

Control structures change that up a bit. This lesson, we'll be showing you how to write programs that decide what code to run. This is called the control flow of the program, or which "path" the program takes. Think of it like a fork in the road–you decide to either go right or left.

How Do Computers Make Decisions?

Computers make decisions a little differently from humans. When I choose what I'll eat for lunch, I need to ask myself a few questions: What do I want? How much am I willing to spend? How convenient is it for me to get it? All these questions have an infinite number of answers.

However, as you might remember from lesson 2, computers operate on an on-or-off basis–this means that each question can only have two answers, true or false, or 0 or 1. In C++, there's a data type for that–the boolean, or as we would write the type, bool! In summary, each question our program has to answer needs to have a boolean answer, either true or false.

To review over the boolean type, revisit the variables walkthrough section and scroll to the table

Relational Operators

Thankfully, C++ gives us a few predefined "questions" in the form of relational operators. These compare two pieces of data and evaluate to a boolean type–exactly what we're looking for! For simplicity's sake, we will only use relational operators on numbers for now, so we will be comparing the values of numbers. You might recognize some of these from math, they work the same way:

| Relation | Operator |

|---|---|

| Equal to | == |

| Not equal to | != |

| Less than | < |

| Greater than | > |

| Less than or equal to | <= |

| Greater than or equal to | >= |

To use these, we'll have to place two operands, what the operation is performed with, on either side. These work a lot like the arithmetic operators from last lesson. Just as 4 + 5 equals 9, 3 < 4 equals true. Here are some examples. Pay attention to what questions they ask and what they evaluate to.

| Code | Asks this question… | Which evaluates to… |

|---|---|---|

| 2 == 3 | Is 2 equal to 3? No. | false |

| 3 != 5 | Is 3 not equal to 5? Yes. | true |

| 4 < 5 | Is 4 less than 5? Yes. | true |

| 10 > 12 | Is 10 greater than 12? No. | false |

| 3 <= 3 | Is 3 less than 3 or equal to 3? Yes, equal. | true |

| 4 >= 5 | Is 4 greater than 5 or equal to 5? No, neither. | false |

Alright, now we have a boolean answer to a question. How do we use it?

if Statements

The if statement allows the program to decide whether or not to execute a block of code, depending on a boolean condition. The basic structures looks like this:

if (condition)

{

//code goes here

}

If the boolean condition is true, the program will execute everything inside of the curly braces. If the condition isn't true, the program simply skips to the next line of code after the if-block (after the closing }).

This condition can be anything that evaluates to a boolean type–a variable, a literal (true or false), or any of the relational operators mentioned above. The condition should be surrounded by parenthesis, and the code that is run conditionally needs to be enclosed inside curly braces:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int temperature;

cin >> temperature;

if (temperature > 80)

{

cout << "It's hot outside!" << endl;

}

cout << "Program done." << endl;

}

This code lets a user input a temperature in Fahrenheit and outputs It's hot outside if the temperature is greater than 80 degrees. Regardless of what the temperature is, the program will always output Program done. This is because the second cout isn't part of the if statement's code block, so it's executed right after the if block is evaluated.

Although we mentioned previously that the code that is executed in the if block must be enclosed by curly braces, if the code that needs to be executed is only one line, we can use an alternative syntax. We could replace the if statement in the above code with:

if (temperature > 80)

cout << "It's hot outside!" << endl;

This code would run the exact same, but the benefit is that it is a bit shorter and more readable. Any lines after the single line, even if indented will not be considered part of the if block.

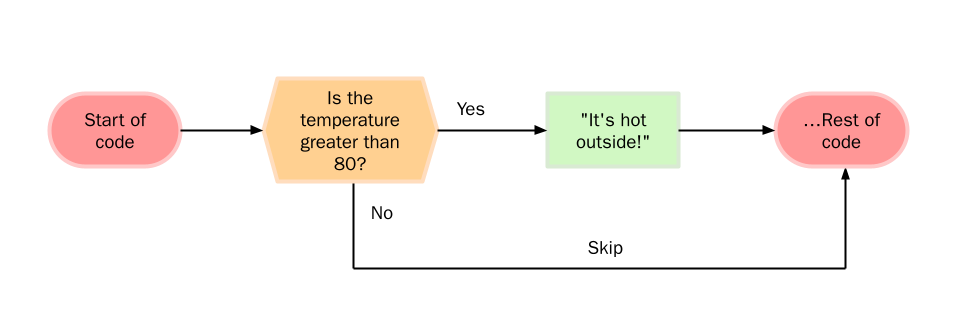

We can use a flowchart to visualize the control flow of the program. This is especially useful with more complex programs–you'll see this later

Any amount of code can be put inside an if block–it just needs to be enclosed in the curly braces. Also note the indentation–while it's not required by C++, it lets the programmer know what is and isn't inside the if block.

else and else if clauses

else clause

An if statement allows a program to either run or skip over a run of code. What if we wanted the program to choose between two blocks of code to run? The else clause can help us do that. When put after an if statement, the program will run the code when the condition is not met. Let's take our existing temperature code and output something if the temperature is not greater than 80:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int temperature;

cin >> temperature;

if (temperature > 80)

cout << "It's hot outside!" << endl;

else

cout << "It's not hot outside!" << endl;

cout << "Program done." << endl;

}

The else clause is placed immediately after the if block we want to apply it to. In the code above, if the temperature is greater than 80, the condition is false and outputs It's hot outside! just like our old code did. If the temperature is less than or equal to 80, the condition becomes false and the code in the else block is run, which outputs It's not hot outside!.

Also notice how we did not include the curly braces with the if and else block since we are only running a single line of code. If we wanted to run more than one line of code, we would need to include the curly braces.

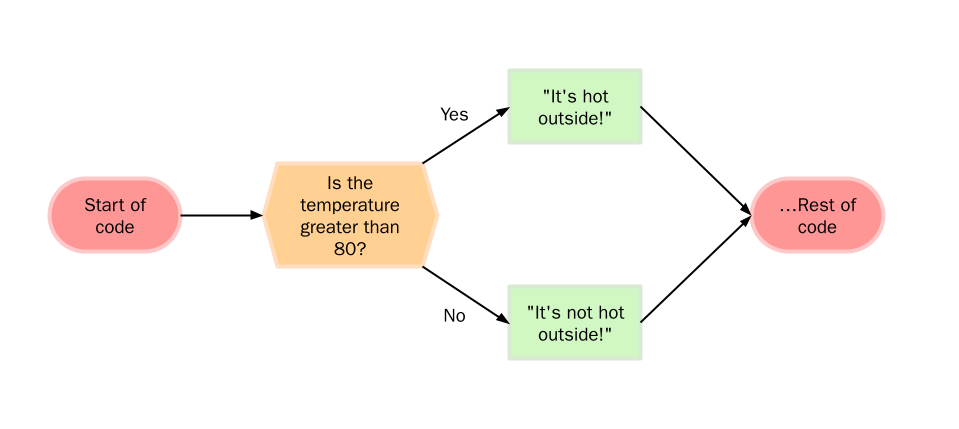

The flowchart looks like this:

else if clauses

The else if clause lets us check for another condition of the preceding if condition is false. This lets the program make more complex decisions by testing multiple boolean conditions. Let's modify our program to also test if the temperature is below freezing:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int temperature;

cin >> temperature;

if (temperature > 80) {

cout << "It's hot outside!" << endl;

else if (temperature < 32)

cout << "It's freezing outside!" << endl;

else

cout << "It's neither hot nor freezing outside!" << endl;

cout << "Program done." << endl;

}

The program first checks if the temperature is above 80. If it is, the program outputs It's hot outside! and skips to Program done. However, if the temperature isn't above 80, the program moves onto the else if clause. Here, we test if the temperature is below 32–if it is, It's freezing outside! is outputted and we move to Program done.

Finally, if the temperature is neither above 80 or below 32, the program outputs It's neither hot nor freezing outside! and then moves to Program done.

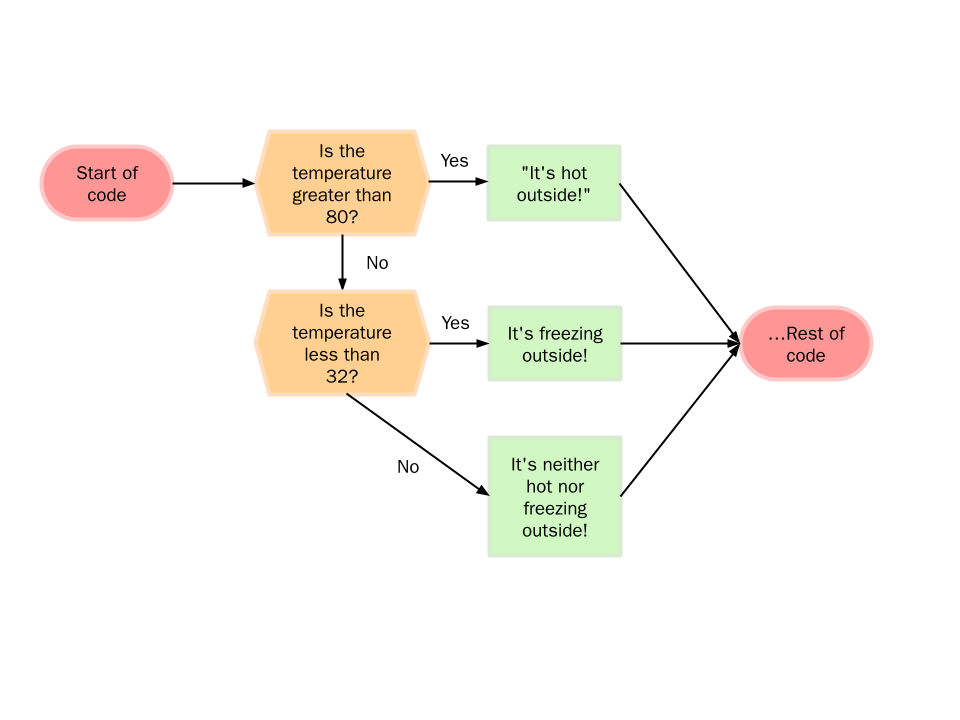

The flowchart looks like this:

The flowchart is a little complex, but the main takeaway here is that order matters. We're first checking if the temperature is greater than 80, then we're checking if the temperature is less than 32. This matters sometimes–consider this example:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int temperature;

cin >> temperature;

if (temperature > 80)

cout << "It's hot outside!" << endl;

else if (temperature > 90)

cout << "It's really hot outside!" << endl;

cout << "Program done." << endl;

}

If we enter 95, the program outputs It's hot outside! because the program first checks if the temperature is greater than 80. It is, so it'll print It's hot outside! despite the else if clause. If we reverse the order of the conditions, we get different behavior:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int temperature;

cin >> temperature;

if (temperature > 90)

cout << "It's really hot outside!" << endl;

else if (temperature > 80)

cout << "It's hot outside!" << endl;

cout << "Program done." << endl;

}

Now if we enter 95, the program outputs It's really hot outside! because we first check if the temperature is greater than 90, then if it isn't, we check if it's greater than 80. Usually this is what we want, so pay attention to the order of if clauses.

Another thing to note: in our original code, the undesired behavior only appears when we enter a number between 80 and 90. These errors can be difficult to find since we encounter a problem only for certain inputs.

Boolean Operators

What if we want to check for multiple conditions? This is where boolean operators come in. These allow us to invert and combine conditions to perform more complex logic. C++ has three main boolean operators:

| Operator | C++ Syntax | Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| NOT | ! | Inverts the condition |

| AND | && | true only if both sides are true |

| OR | || | true if either side is true or if both sides are true |

The NOT operator is the simplest: it simply inverts a single boolean condition, turning true into false and vice versa. AND and OR operate on two boolean conditions, becoming true when both are true (AND) or when either are true (OR). Here are some examples:

| Code | Evaluates to... | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

!(3 < 5) | false | 3 < 5 evaluates to true and is inverted by NOT, so we get false. |

10 < 20 && 20 > 40 | false | 10 < 20 is true, but 20 > 40 is false. Both need to be true for an AND operator to evaluate to true, so this expression evaluates to false. |

10 < 20 || 20 == 40 | true | 10 < 20 is true and 20 == 40 is false. Only one boolean condition needs to be true for an OR operator to evaluate to true, so this expression evaluates to true. |

These can be used inside if and else if clauses just like we'd normally use a condition. This is helpful if we want to check a single variable for multiple conditions, or check multiple variables. Consider this example, where we use the && operator to determine whether a number is between 5 and 20, exclusive:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int number;

cin >> number;

if (number > 5 && number < 20)

cout << "Between 5 and 20" << endl;

else

cout << "Not between 5 and 20" << endl;

}

Also note the else clause. If our number is not greater than 5 and less than 20, then we know that our number is not between 5 and 20. Therefore, another way we could check if a number is between 5 and 20 is checking if it is less than or equal to 5 or greater than or equal to 20, and inverting it with the NOT operator:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int number;

cin >> number;

if (!(number <= 5 || number >= 20))

cout << "Between 5 and 20" << endl;

else

cout << "Not between 5 and 20" << endl;

}

Often times with boolean operators, there are multiple ways to accomplish the same thing. Try to choose the one that clearly communicates your intentions and is simpler: the first example is simpler, and by looking at it we can see that we're checking for a number between 5 and 20.

Order of Precedence

Just like arithmetic operators, boolean operators also exhibit an order of precedence. The order is:

NOT, AND, OR

This is important to note when we have multiple OR and AND next to each other:

false && true || true

This evaluates to true. First we evaluate false && true which evaluates to false. Then we get false || true which evaluates to true.

We can override this order of precedence with parenthesis.

false && (true || true)

This evaluates to false because this time we first evaluate true || true which turns into true, but then false && true evaluates to false.

However, even though we know that the && in the initial example is evaluated first, a more readable form of code might be to use:

(false && true) || true

We can add to the table we previously made in the last lesson with all these new operators:

| Precedence | Operator | Description | Associativity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | ++ -- () (type) function() | post-increment post-decrememnt parentheses type cast function call | left to right |

| 3 | ++ -- ! | pre-increment pre-decrement not | right to left |

| 5 | * / % | multiplication division modulus | left to right |

| 6 | + - | addition subtraction | left to right |

| 9 | < <= > >= | less than less than or equal to greater than greater than or equal to | left to right |

| 14 | && | AND | left to right |

| 15 | || | OR | left to right |

Again, the precedence is evaluated least to greatest. There are missing numbers that we will slowly fill in as we progress through these lessons.

Nested if statements

C++ allows if statements inside of other if statements. This can be used to create a complex, menu-like behavior inside code, where we make decisions as a result of other decisions:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int x = 3

int y = 11

if (x == 3)

{

if (y < 10)

cout << "Hello moon" << endl;

else

cout << "Hello sun" << endl;

}

else

{

if (y == 10)

cout << "Hello Earth" << endl;

else

cout << "Hello Solar System";

}

}

This code prints out Hello sun. First the program checks the value of x. it is equal to 3, so we go into the outer if block. Then the program checks the value of y, which is not less than 10, so the program goes into the first inner else block and prints out Hello sun.

Boolean Operators or Nested if?

Sometimes it's possible to use either boolean operators or nested if blocks to create our desired behavior. However, one method may be easier to follow, easier to edit, or faster (computing-wise) than the other. The guiding question when choosing is whether the decisions we want our program to make are flat or hierarchical.

Here's an example: to navigate to this guide, you probably had to go to our course page, click on "Intro to C++", and the click on "Conditionals.". What lesson you clicked on depended on what course you clicked on. If you clicked on "Intro to Python" and then clicked "Conditionals", you'd be looking at a different webpage. This would be a hierarchical style.

Therefore, it would make sense to use nested if statements here, as your second decision depends on what category you chose in the first.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

string course;

string lesson;

if (course == "Intro to Python") {

if (lesson == "Introduction")

cout << "Intro to Python Introduction" << endl;

else if (lesson == "Conditionals")

cout << "Intro to Python Conditionals" << endl;

}

else if (course == "Intro to C++") {

if (lesson == "Introduction")

cout << "Intro to C++ Introduction" << endl;

else if (lesson == "Conditionals") {

cout << "Intro to C++ Conditionals" << endl;

}

}

The maximum number of decisions our program needs to make is 2. One for the course, and one for the lesson. Conversely, if we used boolean operators here, we would need a single if statement with three else if blocks, meaning at the worst case we'd need to make four decisions. This is slower, and the code is uglier. It would represent a flat decision making scheme:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

string course;

string lesson;

if (course == "Intro to Python" && lesson == "Introduction")

cout << "Intro to Python Introduction" << endl;

else if (course == "Intro to Python" && lesson == "Conditionals")

cout << "Intro to Python Conditionals" << endl;

else if (course == "Intro to C++" && lesson == "Introduction")

cout << "Intro to C++ Introduction" << endl;

else if (course == "Intro to C++" && lesson == "Conditionals")

cout << "Intro to C++ Conditionals" << endl;

}

switch statements

switch statements are another way for a program to decide what code to run. A switch statement accepts a variable and jumps to a block of code based off what value it's equal to.

A switch statement can replace lengthy if and else if clauses making the program easier to read and even sometimes a little faster. However, main caveat is that switch statements can only test if a variable is equal to a constant or literal. Furthermore, that variable needs to be an integer or char.

Consider this example, where a switch statement is used to print a value based off the value of a char.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

char c;

cin >> c;

switch (c)

{

case 'a':

cout << "First vowel of the alphabet" << endl;

break;

case 'e':

cout << "second vowel of the alphabet" << endl;

break;

case 'i':

cout << "Third vowel of the alphabet" << endl;

break;

case 'o':

cout << "Fourth vowel of the alphabet" << endl;

break;

case 'u':

cout << "Fifth vowel of the alphabet" << endl;

break;

default:

cout << "Not a vowel" << endl;

break;

}

}

If c has the value 'a', the code under case 'a': is run. If c has the value 'e', the code under case 'e': is run, and so on. If c is not a, e, i, o, or u, the default: case is done and Not a vowel is printed.

Note that there's a break after every case. This tells our program to jump to the end of the switch statement after each case is executed. If the break wasn't present, our switch statement would fall through, and each case would also execute all the cases below it.

This can be done with a large if/else-if/else tree, but the code is both harder to read and slower. To understand why switch statements are faster in these scenarios, consider this example:

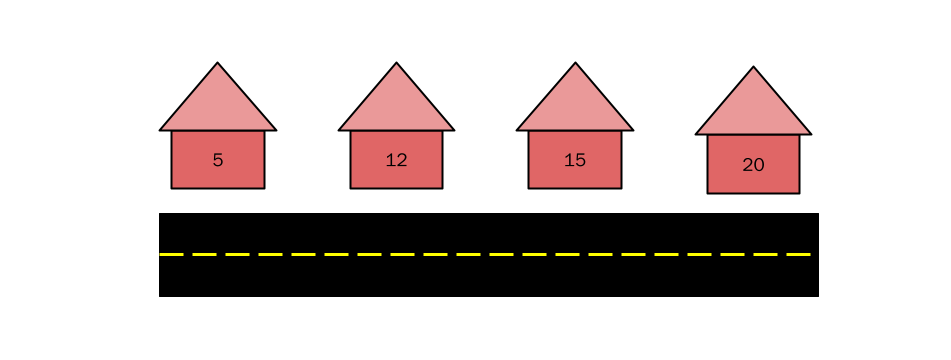

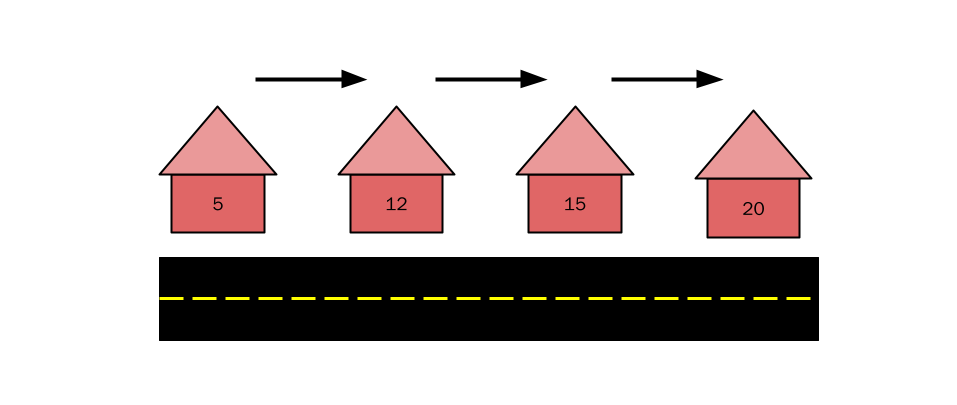

You're on a street and want to find house #12. However, none of the houses on the street have street numbers! Worse, the houses aren't in order, so we can't know the other house numbers off of one:

We could either walk to each house, ring the doorbell, and ask for the house number,

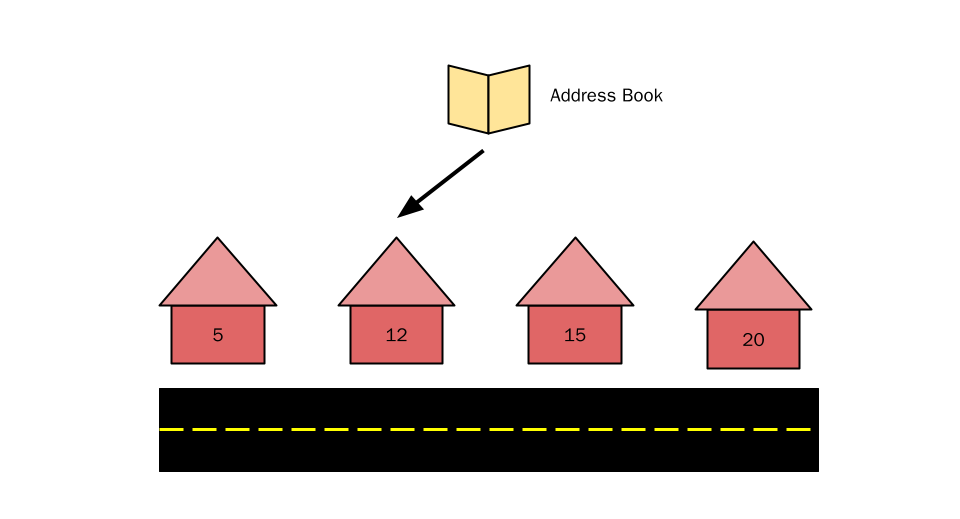

Conversely, if we had an address book, we could simply look at the address book, find the houes number, and directly go to the house:

Conversely, if we had an address book, we could simply look at the address book, find the houes number, and directly go to the house:

| House number | Where is it? |

|---|---|

| 5 | 1st house |

| 12 | 2nd house |

| 15 | 3rd house |

| 20 | 4th house |

This is exactly what a switch statement does: it generates a jump table that acts like an address book and allows the program to jump to a specific branch of the switch statement. This is why switch statements only work on ints and chars: the compiler needs to know what the value is in order to generate a jump table. It also needs to know what they are at compile time which is why they must be const or literal.

If we were to implement the house example in C++, our code would look like this:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int house;

if (house == 5)

cout << "Found house 5..." << endl;

else if (house == 12)

cout << "Found house 12..." << endl;

else if (house == 15)

cout << "Found house 15..." << endl;

else if (house == 20)

cout << "Found house 20..." << endl;

}

If we wanted to find house 20, we'd need to make 4 comparisons. Although this is the worst-case scenario, generally if/else blocks will be slower on average than if we used a switch statement:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int house

switch (house)

{

case 5:

cout << "Found house 5..." << endl;

break;

case 12:

cout << "Found house 12..." << endl;

break;

case 15:

cout << "Found house 15..." << endl;

break;

case 20:

cout << "Found house 20..." << endl;

break;

}

}

In this example, no matter what house number we're trying to get to, the time to access the block of code is the same.

The Ternary Conditional

The previous operators we have dealt with only take two operands. This operator takes three operands, hence the ternary. We use the ternary conditional as a short form for if/else blocks, but the key difference is that the ternary operator is evaluated as an expression - you can use it like an arithmetic operator.

The syntax of the operator looks like this

result = condition ? value if true : value if false

This code returns 10 if the a < b and 20 otherwise:

// a and b are initialized above

int result = a < b ? 10 : 20;

Note that we can directly assign the evaluated result of the ternary conditional operator to a variable.

For example, consider if you wanted to create a variable that must be less than 10. If the user inputs a value that is greater than 10, you want the value to be 10, otherwise it can be set to that value. Using an if-else the code would be rather awkward:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int in, out;

cout << "Enter a number: ";

cin >> in;

if (in > 10)

out = 10;

else

out = in;

cout << "Output: " << out << endl;

}

Using the ternary conditonal operator, the code is a lot simpler:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int in, out;

cout << "Enter a number: ";

cin >> in;

out = in > 10 ? 10 : in;

cout << "Output: " << out << endl;

}

Also, if we wanted to declare a variable and initialize it in a single line depending on something else, we would not really be able to do that with if/else. We would need a ternary operator to do something like this in the previous code:

int out2 : in > 10 ? 10 : in;

If we were to try to do this in an if/else block, we would run in to the issue of scope. Declaring a variable inside an if/else block is local to that block. It can only be used inside of that section of the code.

This is they key difference of an if/else block and a ternary operator: the ternary conditional operator evaluates to something. An if/else block only runs the corresponding code block.

The ternary conditional operator is extremely powerful and allows us to simplify code and make it a lot more readable. To decide whether you should use if/else or the ternary conditional operator, ask yourself whether you want to select a particular value. If you do, then use the ternary operator. Otherwise, just use if/else.

Also note that you can nest the ternary conditonal operator. However, doing so is not recommended as it makes the code a lot less readable. Most of the time if you need to nest the ternary operator, the code would be better written in if/else blocks.